Land – The Head-Right System

While researching ancestors living in Colonial Virginia during the 17th century, I found several records of land grants. These records included notations indicating the land grant was made for “transporting” a number of people. Further research led me to discover that several of my ancestors received land from the British government under a program called the “head-right” system. This program began in Virginia in 1618 but eventually was implemented in all the early American colonies. [1]

In The Beginning

The head-right system offered grants of land to those who sponsored an immigrant, indentured, or enslaved person’s voyage to the British colonies in America. Non-resident sponsors received grants of 50 acres per person, including for themselves. Resident sponsors received 100 acres per person. These awards were given for men, women and children, but only men could be sponsors and receive grants that could then be exchanged for land. (Although I have found exceptions.) [1]

The people being sponsored were labeled as ‘head-rights‘. The sponsor was called the patentee, because he received a ‘patent‘ (a grant) for the land he could later claim. It cost about 6 Pounds (British money) to pay a persons’ voyage. For instance, a man could emigrate with his wife and, say, 4 children and receive a 300 acre land grant for the cost of the voyage, about 36 Pounds. This would be equivalent to about $8000 today, according to one estimate. [2] This amount was much more than most Britain’s made in a year. It was the wealthy, or at least merchant-class, who could afford to pay passage for their family.

Tobacco

The need for cheap labor was due to the new tobacco industry. When Europeans came to North America, the Native Americans showed them the tobacco plant and how they dried it and smoked it. The Europeans took dried leaves back to Europe and soon smoking tobacco in pipes became very popular. The large population of Europe created a large demand for tobacco. This, in turn, created a need to cultivate more tobacco. The weather in Great Britain is not conducive to growing tobacco, so it had to be grown in North America. This gave rise to the head-right system which addressed both the need for cheap labor and the need to expand cultivation.

Land and Labor

Imported laborers, typically single men, had their voyage paid by wealthy sponsors who could afford the 6 Pounds. In exchange, the laborer incurred a debt to repay the sponsor. Many of the free people being brought over were indentured to the patentee for a period of 5 to 7 years until the debt for the voyage was repaid. So, in addition to getting the land, the sponsor/patentee was often repaid through labor. And, if a patentee paid the voyage of an enslaved person, they not only received the land grant, they could sell the enslaved person or own them and benefit from their labor forever. Plus, the labor of their descendants! [3]

A sponsor could get land, the labor to work the land, and repayment of their investment. For the indentured head-rights, many received their own land grant once they repaid the debt for their passage. The land the labor-class could claim was typically on the frontiers of the colonies. Of course the enslaved head-rights would never receive anything. The head-right system accelerated the expansion and settling of the British Colonies. But it also contributed to the creation of the wealth-class and institutionalized slavery in America.

A complete discussion of the head-right system is beyond the scope of this post. Please refer to these websites to learn more.

http://www.virginiaplaces.org/settleland/headright.html

https://historyplex.com/headright-system-facts-significance

John Major (1607-1648)

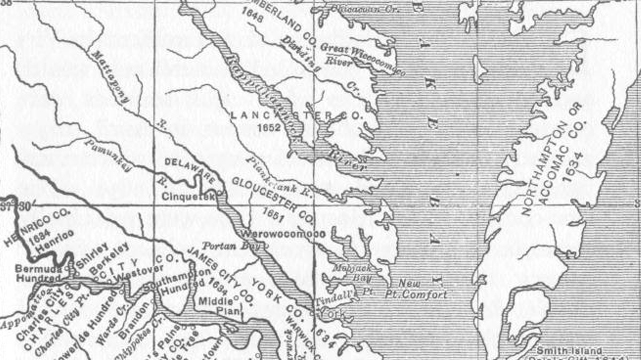

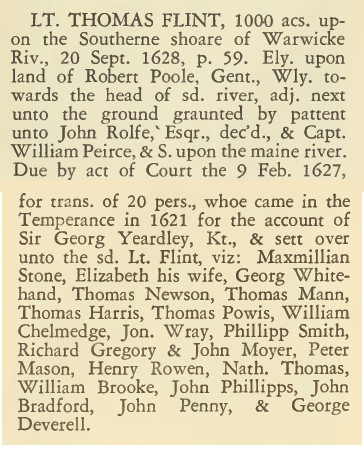

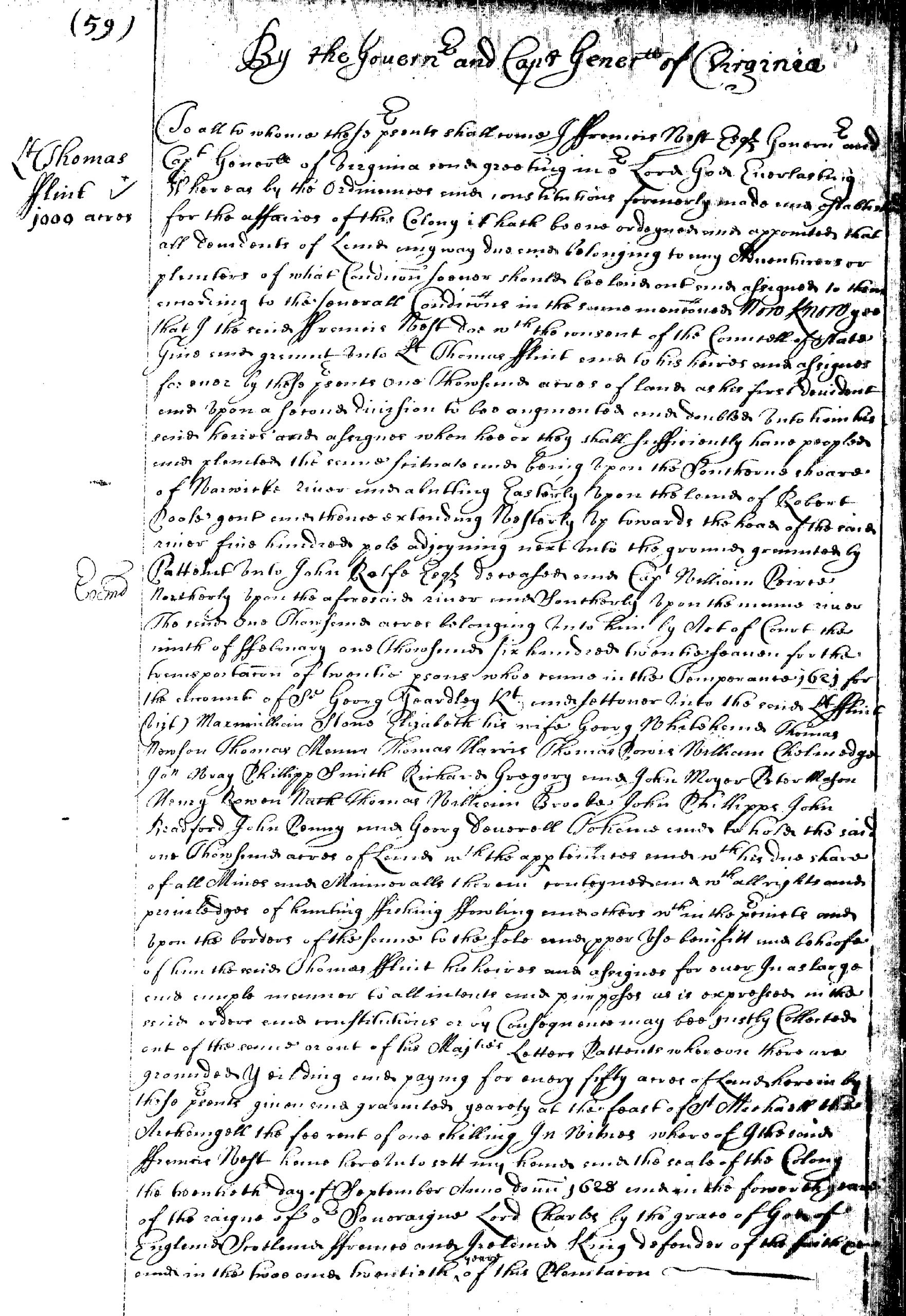

My 10th great grandfather, John Major [4], was a head-right of Sir George Yeardley, along with 19 other people, arriving in the ship Temperance in 1621 at Jamestown, Virginia. [5, 6] Yeardley later signed the head-right over to Lt. Thomas Flint. Lt. Flint exercised the patent/grant on 20 September 1628 for a total of 1000 acres. Land deeds at that time were defined using a system of ‘metes and bounds’. This system uses landmarks to identify property rather than longitude and latitude, as we do today, to create plats. The land Lt. Flint received was described as “being upon the Southern shore of Warwicke River. Easterly upon the land of Robert Poole. Westerly towards the head of said river, adjacent unto the ground granted by patent to John Rolfe, Esq., deceased. Southerly upon the Maine River.”

Head-Rights

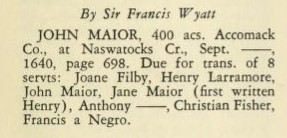

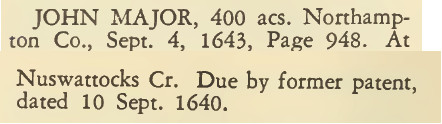

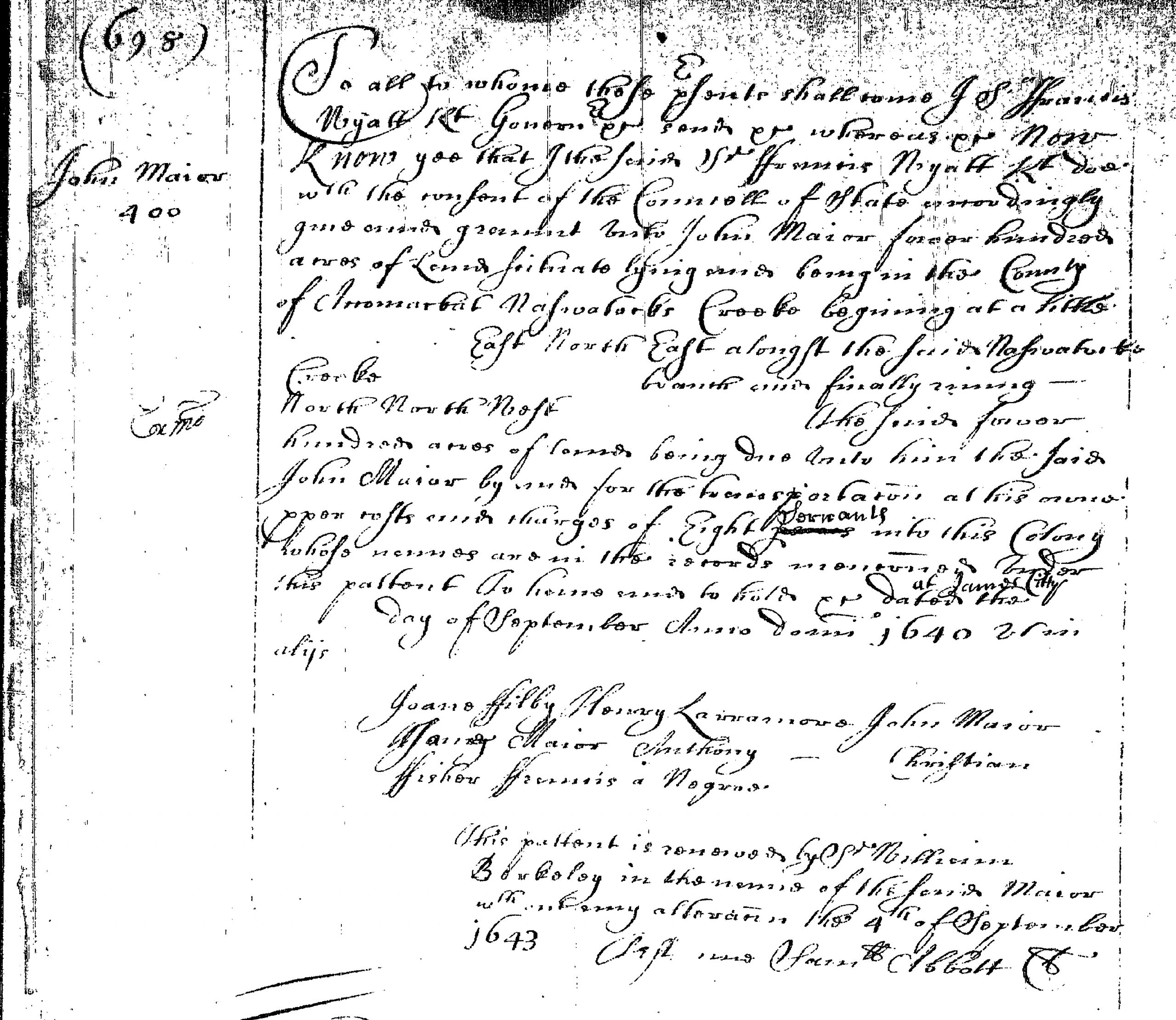

John Major was also able to make use of the head-right program to his own advantage. In 1640, John was able to claim eight persons under the system for a total of 400 acres. [7] The 8 head-rights in John Major’s patent were described as ‘servants‘, although; on the list is John, his wife and his father-in-law Henry Laramore. Then, in 1643 John exercised his patent for land on Nuswattocks (now Nassawadox) Creek in Northampton County, VA. [8]

Conclusion

Head-rights, tobacco and slavery are intertwined in the European settlement of Virginia. Would any one of these existed if not for the other? Without the demand for tobacco the head-right system may have still existed, since it was a good incentive to pay the passage for colonists. But, would land acquisition, by the 100’s of acres, have been important without tobacco? And the need for cheap labor and the introduction of slavery, would that have happened without tobacco? It’s probable that British, and other Europeans, would have eventually immigrated to Virginia and establish a growing colony even without the tobacco industry. But, it may have happened in a way more similar to the settlement of New England. That is, a merchant-class and subsistence farming without the head-right system or slavery.

Additional Online Resources for Researching 17th Century Virginia

Land Patents

https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/opac/lonnabout.htm

https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/bibguides.htm

Compiled List of Immigrants

“Early Virginia Immigrants”, by George Cabell Greer, Pub: W.C. Hill Printing Company

https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=xDISAAAAYAAJ

Accomac County

“Ye Kingdome of Accawmacke”, Jennings Cropper Wise, Pub: Bell Book and Stationery Company

https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=HDATAAAAYAAJ

SOURCES

- https://historyplex.com/headright-system-facts-significance

- https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/ppoweruk/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Headright

- Profile for John Major, ‘Osborn‘ family tree, Ancestry.com;

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/13493206/person/12748823129/facts - “Cavaliers and Pioneers; Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants, 1623-1800”, abstracted and indexed by Nell Marion Nugent, Pub: Press of the Dietz Print Co. of Richmond, VA, 1934; page: 10; [Cavs/Pios]

Vol, 1 (1623-1666), Accessed Online: http://www.archive.org/details/cavalierspioneer00nuge - “The Majors and Their Marriages”, by James Branch Cabell, Pib: W. C. Hill Printing Company, January 1915; page: 28;

Accessed Online: https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=puQ1AAAAMAAJ - ibid Cavs/Pios; page: 119;

- ibid Cavs/Pios; page: 152;

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

I love learning about history